Chest pain is a common symptom that can be concerning, as it is can be associated with heart-related issues. However, it’s important to note that not all chest pain is related to heart problems. In fact, studies have shown that a significant proportion of chest pain cases are not due to a heart-related issue. For example, research has shown that musculoskeletal issues, such as muscle strains or costochondritis, can be a common cause of chest pain. Gastrointestinal issues, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), can also mimic heart-related chest pain in some cases. Feel free to also watch our Youtube video below where we go through how a Cardiologist evaluates the various causes of chest pain.

In this article, we will explore chest pain in detail, including its symptoms, causes, and evaluation process. Always remember, chest pain may be a sign of an underlying heart attack so if you are feeling unwell with persisting pain, please contact your local emergency service number for urgent advice.

Understanding Chest Pain

Chest pain can range from mild discomfort to severe pain, and it may present in different ways depending on the underlying cause. It may feel like pressure, squeezing, burning, sharp or stabbing pain in the chest, and it can sometimes spread to the arms, neck, jaw, shoulder, or back. Chest pain can also be accompanied by other symptoms such as shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, sweating, lightheadedness, or palpitations.

Cardiac causes of chest pain

Angina is a chest pain type that arises when the heart muscle doesn’t receive enough oxygen-rich blood. The cause is usually the narrowing of coronary arteries due to fatty deposits named plaques on their inner walls. These plaques can limit blood flow to the heart, especially during physical activity when the heart needs more oxygen. This can lead to chest discomfort, pain, tightness, heaviness or pressure, commonly felt in the chest but possibly extending to the arms, neck, jaw, shoulder, or back. Angina is often described as a squeezing, burning, or heavy sensation in the chest. Emotional stress, physical exertion, or exposure to cold weather can trigger it. Angina comes in different types: stable angina – occuring with exertion and unstable angina that occurs at rest. It’s crucial to recognize that angina signals an underlying heart issue and should not be disregarded. Seeking proper medical evaluation and management is essential to prevent a potential heart attack.

Illustration depicting the narrowing of a coronary artery due to the presence of fatty deposits known as plaques. This constriction of the artery’s lumen reduces the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle, leading to the characteristic chest pain and discomfort associated with angina.

Heart attack: A heart attack, also known as myocardial infarction, occurs when the blood flow to a part of the heart muscle is blocked, usually by a blood clot that forms over a ruptured plaque in a coronary artery. The blockage can cause permanent damage to the heart muscle if not promptly treated. Chest pain is a common symptom of a heart attack and is often described as a crushing, squeezing, or heavy sensation in the chest that may also be accompanied by shortness of breath, nausea, lightheadedness, cold sweats, or pain radiating to the arms, neck, jaw, shoulder, or back. However, it’s important to note that not all heart attacks present with typical chest pain, and symptoms can vary widely between individuals, especially in women, older adults, and people with diabetes. Prompt medical attention is crucial if a heart attack is suspected.

This visualization illustrates the process of clot formation occurring at a point of arterial narrowing. When a clot develops within the artery, it becomes an acute medical emergency, often indicating a risk to the heart muscle due to reduced or blocked blood flow. Immediate assessment and intervention are imperative to unblock the artery and reinstate proper blood circulation, safeguarding the health of the heart.

Aortic dissection: Aortic dissection is a rare but life-threatening condition that occurs when the inner layers of the aorta, the main artery that carries blood from the heart to the rest of the body, tear or separate. This can cause blood to flow between the layers of the aortic wall, creating a false channel and potentially leading to a rupture of the aorta. Aortic dissection typically causes sudden and severe chest pain that is often described as tearing, ripping, or stabbing in nature. The pain may be felt in the chest or upper back and may radiate to the neck, jaw, abdomen, or limbs. Other symptoms may include shortness of breath, difficulty speaking, weakness, loss of consciousness, or signs of shock. Aortic dissection is a medical emergency that requires immediate medical attention.

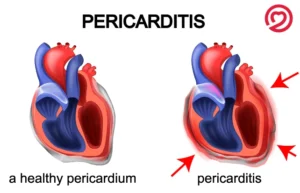

Pericarditis: Pericarditis is the inflammation of the pericardium, the sac-like lining around the heart. It can be caused by viral or bacterial infections, autoimmune diseases, chest trauma, certain medications, and more commonly also seen in the setting of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Chest pain is a common symptom of pericarditis and is often described as sharp, stabbing, or pleuritic, meaning it worsens with deep breaths or lying down. The pain is typically located in the center or left side of the chest and may also radiate to the neck, shoulder, back, or abdomen. Other symptoms of pericarditis may include fever, rapid heartbeat, difficulty breathing, fatigue, dry or productive cough, or a rubbing or grating sound heard with a stethoscope.

A comparison between a healthy pericardium and an inflamed pericardium. The pericardium, a double-layered protective fluid-filled membrane surrounding the heart, is depicted in both images. On the left side, the normal pericardium provides support and prevents the heart from over-expanding. On the right side, the inflamed pericardium is shown, highlighting the effects of pericarditis—an inflammation of this protective membrane. Pericarditis can lead to chest pain and discomfort due to the irritation of nerve endings within the pericardium.

Pericarditis is usually managed with medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and sometimes corticosteroids or colchicine may be prescribed in more severe cases (this medicine is frequently used in gout, a type of arthritis) and works to reduce pain and inflammation and therefore very effective to manage pericarditis. It may be continued for a few months following an acute attack to reduce the risk of recurrence. Treatment may also involve addressing the underlying cause of the inflammation, such as treating an infection or managing an autoimmune condition.

Myocarditis: Myocarditis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the heart muscle (myocardium). This inflammation can be triggered by viral infections, bacterial infections, certain medications, autoimmune disorders and, more recently there has been associations with COVID-19 infections and mRNA vaccines. As the immune system responds to the infection or triggers, it can inadvertently target the heart muscle, leading to inflammation. The inflamed heart muscle may become weakened and have difficulty pumping blood efficiently, which can result in chest pain, shortness of breath, and even palpitations. Recognizing the symptoms of myocarditis and seeking medical attention promptly is crucial to prevent potential complications and ensure appropriate treatment. Diagnostic tests such as electrocardiograms (ECGs), echocardiograms, and blood tests can aid in confirming the presence of myocarditis and guiding the management process.

Non-cardiac causes of chest pain

While chest pain can be associated with heart problems, there are many other potential causes. Some of the most common causes of chest pain include:

Musculoskeletal issues: Chest pain can be caused by muscle strains, ligament injuries, or inflammation of the chest wall, which may occur due to trauma, overuse, or musculoskeletal conditions such as costochondritis or fibromyalgia. Costochondritis: This condition involves inflammation of the cartilage that connects the ribs to the breastbone, resulting in localized chest pain that may worsen with movement or deep breaths. It can be triggered by injury, strain, or infection. Chronic pain syndromes like fibromyalgia can cause widespread musculoskeletal pain, including in the chest muscles, along with other symptoms such as fatigue and sleep disturbances. Injured ribs: Bruised or broken ribs due to trauma, such as a fall or direct impact, can cause localized chest pain that may worsen with breathing, coughing, or touching the affected area.

Gastrointestinal issues: Chest pain can also be related to the digestive system, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is a condition where stomach acid flows back into the esophagus, causing chest discomfort or burning sensation. This is often referred to as ‘heartburn’ and may also be associated with sour taste or a sensation of food reentering the mouth.

Gallbladder or pancreas problems: Gallstones or inflammation of the gallbladder or pancreas can cause pain that starts in the upper abdomen and may radiate to the chest. Other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal bloating may also be present.

Swallowing disorders: Conditions like achalasia, where the muscles of the esophagus do not properly move food into the stomach, or esophageal spasms, where the muscles of the esophagus contract abnormally, can cause difficulty and pain with swallowing, which may be felt in the chest.

Respiratory issues: Conditions affecting the lungs, such as pneumonia, pleurisy (inflammation of the lining around the lungs), or pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung), can cause chest pain, especially with deep breaths or coughing. This is known as ‘pleuritic’ pain that refers to pain that gets worse with inspiration.

Pulmonary embolism: A blood clot that travels to the lungs and blocks blood flow can cause sudden and severe chest pain, along with symptoms like shortness of breath, rapid heartbeat, and coughing up blood. It requires immediate medical attention as it can be life-threatening.

Pleurisy: Inflammation of the pleura, the thin membrane that covers the lungs, can cause sharp chest pain that worsens with breathing or coughing. It is often caused by viral infections, pneumonia, or other lung conditions.

Collapsed lung: A pneumothorax or collapsed lung can cause sharp, stabbing chest pain that comes on suddenly and may be associated with shortness of breath and decreased breath sounds on one side of the chest. It requires prompt medical evaluation

Other causes:

Shingles: This viral infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus can cause severe pain and a band of blisters that wraps from the back around to the chest area. It typically occurs in people who have had chickenpox before and can be managed with antiviral medications and pain relief measures.

Panic attack: Panic attacks can cause intense fear or anxiety, along with physical symptoms like chest pain, rapid heartbeat, sweating, and difficulty breathing. These episodes can be triggered by stress, anxiety, or panic disorder, and may require medical evaluation and management.

It’s important to note that chest pain can have various causes, and a proper medical evaluation is crucial to determine the underlying cause accurately. If you experience chest pain or any concerning symptoms, always consult with a healthcare professional for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Differential Diagnosis and Evaluation

When evaluating chest pain, healthcare providers use a systematic approach to determine the underlying cause. This may involve a detailed medical history, physical examination, and various diagnostic tests, including:

Electrocardiogram (ECG): An ECG is a non-invasive test that records the electrical activity of the heart and can help identify abnormal heart rhythms or signs of a heart attack.

Blood tests: Blood tests, including cardiac enzymes and markers, can help detect if there has been damage to the heart muscle.

Imaging tests: Imaging tests, such as chest X-ray, CT scan, or MRI, can help evaluate the lungs, heart, and other organs in the chest to identify any abnormalities.

Stress testing: Stress testing involves monitoring the heart’s activity during exercise or with medication to assess its function and detect any signs of reduced blood flow.

Endoscopy: Endoscopy may be performed to assess for gastric or esophageal causes such as reflux or peptic ulcers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, chest pain can have various causes, and not all chest pain is related to heart problems. Understanding the different potential causes of chest pain, including cardiac and non-cardiac causes, is important for accurate evaluation and management. If you experience chest pain or any concerning symptoms, it’s essential to seek medical attention promptly to determine the underlying cause and receive appropriate treatment. Always prioritize your health and well-being, and do not ignore persistent or severe chest pain.