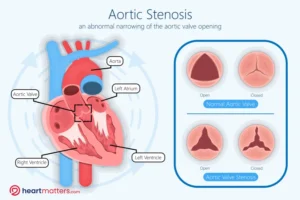

Aortic stenosis is a heart condition that affects the aortic valve, one of the four key valves of our heart. The aortic valve allows blood to travel from the left ventricle to the large artery known as the aorta to supply blood to the body. Aortic stenosis refers to the narrowing of this valve, which restricts blood flow from the heart to the rest of the body. It is one of the most common valve diseases affecting the heart. This article will delve into the various aspects of aortic stenosis, including its symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment options.

What is the Aortic Valve?

The aortic valve is a crucial component of the heart’s anatomy, situated between the left ventricle and the aorta—the body’s main artery. It usually comprises three thin, flexible leaflets or cusps that open and close to regulate blood flow (tricuspid valve), distinct from people born with an aortic valve comprising only two leaflets (bicuspid valve). These leaflets are composed of connective tissue and are supported by fibrous structures called chordae tendineae, which anchor them to the heart’s muscle walls.

The function of the aortic valve is to ensure that blood flows in one direction only, allowing it to exit the heart and enter the aorta to be distributed throughout the body. This valve opens when the heart contracts (during systole), allowing blood to be pumped into the aorta, and closes tightly when the heart relaxes (during diastole), preventing blood from flowing back into the ventricle. The intricate design and function of the aortic valve are essential for maintaining proper circulation and ensuring efficient delivery of oxygen-rich blood to the body’s tissues and organs.

Symptoms of Aortic Stenosis:

The symptoms of aortic stenosis often develop gradually over time, and many people may be unaware of their condition as they do not have any symptoms. Sometimes, the condition may be picked up incidentally by your doctor listening to your heart with a stethoscope or discovered by chance during a heart ultrasound (echocardiogram). However, when symptoms do occur, they may include:

- Chest Pain: Patients may experience chest pain or discomfort, especially during physical activity.

- Shortness of Breath: Breathlessness, particularly during exertion, is a common symptom.

- Fatigue: Feeling fatigued, even after minimal physical activity.

- Dizziness or Fainting: Reduced blood flow to the brain can cause dizziness or fainting spells.

- Heart Palpitations: Irregular heartbeats or sensations of rapid heartbeat may occur.

It’s important to note that the severity of symptoms depends on the degree of valve narrowing, which corresponds to the severity of the valve stenosis.

Therefore, individuals with more severe valve narrowing are more likely to experience pronounced symptoms, while those with milder stenosis may remain asymptomatic or have fewer symptoms. Regular check-ups and screenings are essential for early detection and proper management of aortic stenosis, as prompt intervention can improve outcomes and quality of life. If you experience any of these symptoms or have concerns about your heart health, it’s crucial to consult with a healthcare professional for evaluation and guidance.

Figure: The aortic valve is between the left ventricle and the aorta, the body’s main artery. It is the gateway for blood to exit the heart and enter the circulation system. Open Position of the Aortic Valve: During systole (heart contraction), the aortic valve opens to allow blood to be ejected from the left ventricle into the aorta. The valve’s leaflets are depicted in an open configuration, facilitating blood flow. Closed Position of the Aortic Valve: During diastole (heart relaxation), the aortic valve closes tightly to prevent blood from flowing back into the left ventricle. The valve’s leaflets are shown in a closed position, ensuring unidirectional blood flow and efficient circulation.

Figure: The aortic valve is between the left ventricle and the aorta, the body’s main artery. It is the gateway for blood to exit the heart and enter the circulation system. Open Position of the Aortic Valve: During systole (heart contraction), the aortic valve opens to allow blood to be ejected from the left ventricle into the aorta. The valve’s leaflets are depicted in an open configuration, facilitating blood flow. Closed Position of the Aortic Valve: During diastole (heart relaxation), the aortic valve closes tightly to prevent blood from flowing back into the left ventricle. The valve’s leaflets are shown in a closed position, ensuring unidirectional blood flow and efficient circulation.

Causes of Aortic Stenosis:

Aortic stenosis can develop due to several factors, including:

- Age: Degenerative changes in the valve with age is a primary cause of aortic stenosis, particularly in individuals over 65.

- Congenital Heart Defects: Some individuals are born with aortic valve abnormalities that predispose them to developing stenosis later in life.

- Calcium Deposits: Calcium buildup on the aortic valve can cause it to stiffen and narrow, leading to stenosis.

- Rheumatic Fever: A complication of untreated strep throat, rheumatic fever can damage the heart valves and increase the risk of aortic stenosis.

Diagnosis of Aortic Stenosis:

Aortic stenosis is typically diagnosed through a combination of medical history review, physical examination, and diagnostic tests, including:

- Echocardiogram: This ultrasound test provides detailed images of the heart’s structure and function, allowing doctors to assess the severity of aortic stenosis.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG): This test records the heart’s electrical activity and can help identify abnormalities.

- Cardiac Catheterization: In some cases, a cardiac catheterization procedure may be performed to visualize the heart’s blood vessels and valves directly.

Criteria for Determining Severity:

The treatment approach for aortic stenosis, particularly in cases of severe valve narrowing, is crucial for managing symptoms and improving outcomes. Severe aortic stenosis is determined based on various criteria, including echocardiographic features such as valve area and pressure gradient across the valve.

- Valve Area: The effective orifice area of the aortic valve is a key parameter in assessing stenosis severity using a heart ultrasound scan (echocardiogram). A smaller valve area indicates more severe narrowing and obstruction of blood flow. In severe aortic stenosis, the valve area is typically less than 1.0 square centimeters.

- Pressure Gradient: Another important indicator is the pressure gradient across the aortic valve during systole. This gradient represents the difference in pressure between the left ventricle and the aorta and correlates with the stenosis severity. Higher pressure gradients suggest more significant obstruction to blood flow and indicate severe aortic stenosis.

Treatment Options for Severe Aortic Stenosis:

Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR):

In severe cases of aortic stenosis, surgical replacement of the diseased valve with a prosthetic valve is often recommended. SAVR involves open-heart surgery and is considered the gold standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis, particularly in younger, lower-risk patients or in patients who have multiple valve conditions or suffer from coronary artery disease that can also be managed with a bypass operation.

Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR) has long been regarded as the gold standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis, offering durable and reliable outcomes for eligible patients. While Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) has emerged as a minimally invasive alternative, SAVR remains an essential therapeutic option, particularly for certain patient populations.

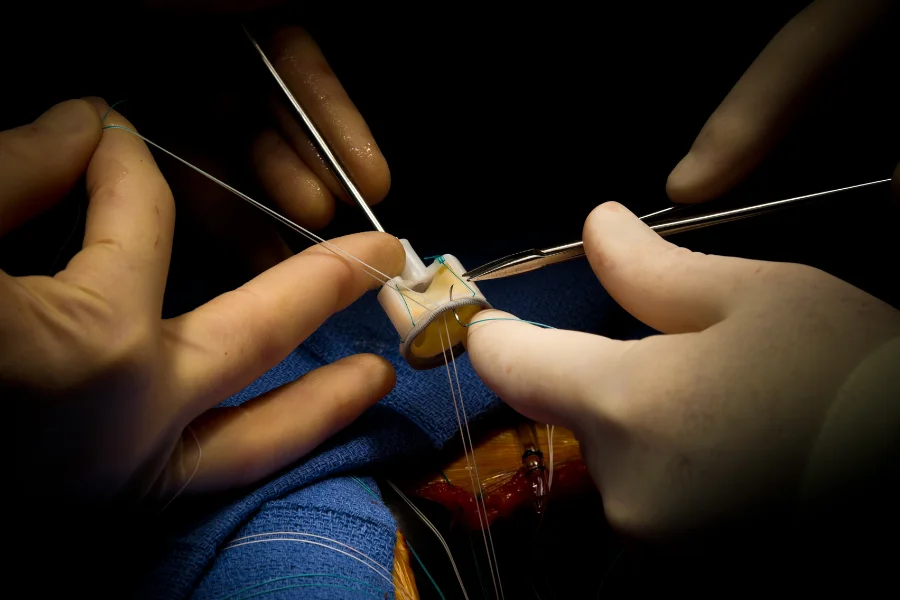

Procedure Overview:

SAVR involves open-heart surgery, during which the diseased aortic valve is removed and replaced with a prosthetic valve. The procedure is performed via a sternotomy or minimally invasive approaches, depending on patient factors and surgical expertise. The new valve may be a mechanical valve made of synthetic materials or a biological valve derived from animal tissue.

Advantages of SAVR:

- Durability: Mechanical valves used in SAVR have demonstrated long-term durability, with a lifespan exceeding two decades in many cases. This durability is particularly advantageous for younger patients who may require a valve replacement with a longer lifespan.

- Complete Valve Removal: SAVR allows for the complete removal of the diseased valve, eliminating the source of obstruction and restoring normal blood flow dynamics. This complete removal may reduce the risk of valve degeneration and long-term complications.

- Customization: SAVR offers the opportunity for customized valve selection and sizing, ensuring optimal fit and function based on individual patient anatomy and characteristics. Surgeons can tailor the procedure to address specific patient needs and preferences.

Considerations for SAVR:

-

- Invasiveness: SAVR is a major surgical procedure that requires sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass, resulting in longer hospital stays, extended recovery periods, and higher perioperative morbidity and mortality compared to TAVR.

- Recovery Time: The recovery period following SAVR is typically longer than that of TAVR, with patients requiring several weeks to months to recover and resume normal activities fully.

- Patient Selection: SAVR may be the preferred option for younger patients without significant comorbidities who are candidates for open-heart surgery. However, older patients or those with multiple comorbidities may be better suited for TAVR due to its less invasive nature and lower procedural risk.

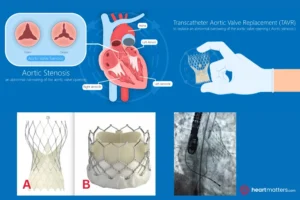

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR):

This represents a significant advancement in treating aortic stenosis, offering a less invasive alternative to Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR). Initially introduced as a solution for high-risk or ineligible patients for open-heart surgery, TAVR has rapidly gained acceptance and expanded its indications to encompass a broader spectrum of patients, including those at low surgical risk.

Procedure Overview:

During a TAVR procedure, a collapsible replacement valve, typically made of biological material such as bovine or porcine tissue, is delivered to the heart via a catheter-based approach. The most common access site is through the femoral artery in the groin, although alternative access routes, such as the transapical or transaortic approach, may be utilized depending on patient anatomy and clinical considerations.

Once the catheter reaches the site of the diseased aortic valve, various techniques are employed to deploy the new valve. This may involve inflating balloons to expand the native valve leaflets and create space for the replacement valve or using a self-expanding stent-valve that expands upon release from the catheter. Once in position, the new valve effectively replaces the diseased valve, restoring normal blood flow from the heart to the rest of the body.

This figure illustrates two commonly used stent valves during a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) procedure: the CoreValve (A) and the Edwards Sapien 3 valve (B). These valves are typically delivered to the aorta through the artery in the groin (femoral artery) using a catheter-based approach. Once positioned at the site of the diseased aortic valve, the stent-valve is expanded inside the native valve, restoring normal blood flow and function.

Evolution of TAVR Usage:

TAVR was initially reserved for patients deemed too high risk for traditional open-heart surgery due to factors such as advanced age, frailty, or multiple comorbidities. However, as clinical experience and procedural techniques have advanced, the safety and efficacy of TAVR have been demonstrated in a wider range of patients, including those at low surgical risk.

Several landmark clinical trials, such as the PARTNER and SAPIEN trials, have provided robust evidence supporting the use of TAVR across various risk categories, leading to the expansion of TAVR indications by regulatory agencies and professional societies worldwide. The FDA approval of TAVR for low-risk patients in 2019 marked a significant milestone in the field, further cementing its status as the standard of care for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis.

Benefits of TAVR:

-

- Minimally Invasive: TAVR offers a less invasive alternative to traditional open-heart surgery, resulting in shorter hospital stays, quicker recovery times, and reduced procedural morbidity and mortality.

- Suitable for High-Risk Patients: TAVR provides a treatment option for patients deemed too high risk for surgery, expanding access to life-saving therapy for a broader patient population.

- Improved Quality of Life: Studies have shown that TAVR significantly improves symptoms, functional status, and quality of life for patients with severe aortic stenosis.

Other treatment options:

Balloon Valvuloplasty:

This procedure may be performed in select cases to temporarily relieve symptoms of severe aortic stenosis, particularly in patients who are not suitable candidates for valve replacement surgery. Balloon valvuloplasty involves inflating a balloon within the narrowed valve to widen the opening and improve blood flow. However, its effects are often temporary, and the procedure is less commonly used as a definitive treatment for severe aortic stenosis.

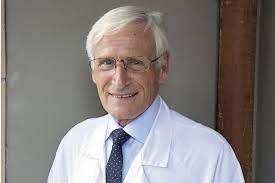

In Memoriam – Professor Alain Cribier (1945 – 2024)

Prof Alain Cribier’s pioneering spirit and unwavering dedication to advancing cardiovascular care through transcatheter interventions have left an indelible mark on the field. As the visionary who first performed aortic balloon valvuloplasty and pioneered Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR), Prof Cribier’s legacy will continue to inspire generations of clinicians and researchers as we strive to push the boundaries of possibility and improve patient outcomes. Among his career highlights, Cribier performed the first balloon aortic valvuloplasty in 1985 but soon realized its initial success would not last because of restenosis. In the 1990s, he began exploring the possibility of using a balloon-expandable valve stent to prevent restenosis and replace the diseased aortic valve. On April 16, 2002, this vision finally became a reality when Cribier and his colleagues performed the first TAVR. Since then, thousands of patients previously considered inoperable have benefitted from TAVR.

Prof Alain Cribier’s pioneering spirit and unwavering dedication to advancing cardiovascular care through transcatheter interventions have left an indelible mark on the field. As the visionary who first performed aortic balloon valvuloplasty and pioneered Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR), Prof Cribier’s legacy will continue to inspire generations of clinicians and researchers as we strive to push the boundaries of possibility and improve patient outcomes. Among his career highlights, Cribier performed the first balloon aortic valvuloplasty in 1985 but soon realized its initial success would not last because of restenosis. In the 1990s, he began exploring the possibility of using a balloon-expandable valve stent to prevent restenosis and replace the diseased aortic valve. On April 16, 2002, this vision finally became a reality when Cribier and his colleagues performed the first TAVR. Since then, thousands of patients previously considered inoperable have benefitted from TAVR.

Timing of Intervention for Severe Aortic Stenosis

Timing of intervention (SAVR or TAVR) is crucial in managing severe aortic stenosis (AS), especially when symptoms develop and the valve becomes severely narrowed. Aortic stenosis is a progressive condition, and once symptoms manifest and the valve becomes severely obstructed, the prognosis can be poor if left untreated. Therefore, prompt intervention is often necessary to improve outcomes and prevent adverse events.

When symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, dizziness, or fainting occur in severe AS, it typically indicates significant obstruction to blood flow out of the heart. This obstruction increases pressure within the heart chambers, compromising cardiac function and reducing blood supply to vital organs.

The timing of intervention depends on various factors, including the severity of symptoms, the degree of valve narrowing, and the patient’s overall health status. Current guidelines recommend heart team discussions with patients to assess the most appropriate intervention, namely surgery or transcatheter valve, for symptomatic patients with severe AS. Delaying intervention can lead to worsening symptoms, heart failure, and increased mortality risk.

If intervention is delayed, the prognosis for patients with severe aortic stenosis and symptomatic disease can be poor. Timely aortic valve replacement, whether through surgical or transcatheter approaches, is essential for improving outcomes and enhancing the quality of life in these individuals. Early recognition of symptoms and proactive management are key to optimizing outcomes and ensuring the best possible prognosis for patients with severe AS.

The decision to intervene in asymptomatic patients with severe AS is more nuanced and involves careful risk stratification and regular monitoring. While early intervention may be considered in specific high-risk individuals or those with rapid disease progression, conservative management with close surveillance is often recommended for patients with stable symptoms and low surgical risk.

Healthcare providers must assess each patient individually, considering their symptoms, functional status, comorbidities, and preferences when determining the optimal timing of intervention. Multidisciplinary heart teams comprising cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and other specialists play a critical role in evaluating patients with severe AS and collaboratively deciding on the most appropriate treatment approach.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, many individuals with aortic stenosis do not receive prompt attention or recognition of their condition. As symptoms of aortic stenosis can be subtle or easily attributed to other causes, individuals must advocate for their health and seek medical evaluation if they experience symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, or fatigue. Speaking with a healthcare professional and undergoing appropriate diagnostic testing can lead to timely diagnosis and intervention, ultimately improving outcomes and quality of life for individuals with aortic stenosis. The landscape of aortic stenosis treatment has undergone a remarkable transformation with the increasing adoption of less invasive procedures such as Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR). These advances have revolutionized the management of severe aortic stenosis, offering viable alternatives to traditional open-heart surgery and expanding access to life-saving interventions for a larger patient population.