Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a condition where the walls of the heart become abnormally thick, leading to a variety of symptoms and potential complications. It’s a relatively common genetic disease that affects people of all ages and can be life-threatening if not managed properly. In this article, we’ll explore the causes, symptoms, and some treatment options of HCM.

Causes

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) stems from mutations in one or more genes, impacting the proteins that govern the heart muscle’s structure. These genetic mutations result in the thickening of heart muscles, impeding the heart’s efficiency in pumping blood. It’s important to emphasize to patients that an enlarged heart muscle isn’t necessarily advantageous and can lead to heart weakening and symptomatic manifestations. HCM follows an inherited pattern and is transmitted within families in an autosomal dominant manner. This signifies that the disease develops with just one copy of the mutated gene, underscoring the genetic link to its occurrence.

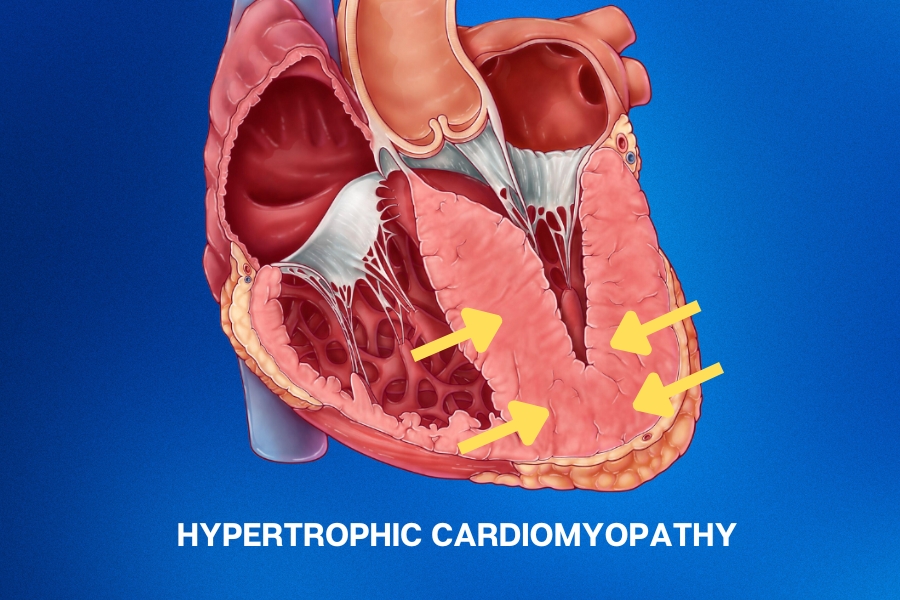

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) leads to the walls of the heart’s main pumping chamber becoming thicker than usual (left ventricular hypertrophy). This can happen without any apparent reasons and is frequently coupled with a non-dilated left ventricle featuring preserved or heightened ejection fraction (a measure of the strength of the heart). One thing about HCM is that it usually makes the heart’s walls thicker unevenly, with the lower part of the wall between the chambers being the most affected (asymmetric septal hypertrophy).

Looking at HCM under a microscope, we see that the heart muscle cells become more extensive, and their arrangement can be disorganized. There’s also some extra fibrous tissue in between these cells. This might lead to the heart’s lower chamber not relaxing as well as it should between beats (known as diastolic dysfunction).

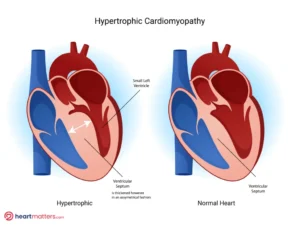

The figure presents a side-by-side comparison of a normal heart and a heart model displaying significant hypertrophy of the interventricular septum, a Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) hallmark. The average heart demonstrates balanced chamber sizes and wall thickness. In contrast, the HCM heart model reveals pronounced thickening of the interventricular septum, indicative of the abnormal structural changes associated with HCM.

Symptoms

Many people with HCM have no symptoms; the condition is only discovered when undergoing a routine medical examination. However, when symptoms do occur, they can include:

- Shortness of breath, especially during physical activity or exertion

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Fainting, especially during physical activity or exertion

- Heart palpitations, which can feel like a rapid or fluttering heartbeat. Atrial fibrillation, a familiar irregular heart rhythm, can also be seen.

- Fatigue or weakness

- Swelling in the ankles, feet, or legs

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

Complications

HCM can lead to a variety of complications, including:

- Arrhythmias: Irregular heart rhythms that can cause the heart to beat too fast or too slow, leading to dizziness, fainting, or even sudden cardiac arrest.

- Heart failure: The thickened heart muscle can make it harder for the heart to pump blood, leading to fatigue, shortness of breath, and fluid buildup in the lungs.

- Obstructive HCM: In some cases, the thickened heart muscle can obstruct blood flow, leading to chest pain, shortness of breath, and fainting.

- Mitral valve regurgitation: is a common observation often associated with HCM. In this scenario, the abnormally thickened heart walls can affect the proper functioning of the mitral valve, leading to the backflow of blood and resultant regurgitation.

Empowering individuals with HCM through knowledge about the genetic facets of the condition and its potential inheritance is paramount for informed decision-making and family health.

Treatment

The treatment of HCM depends on the severity of the condition and the presence of symptoms. In most cases, treatment focuses on managing symptoms and preventing complications. Most HCM patients don’t experience noticeable symptoms and usually don’t need medication. Nevertheless, it’s essential to inform those diagnosed with HCM about the genetic aspect of the condition and the potential for passing it on to their children.

Treatments may include:

- Medications: Beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and other prescribed drugs are adept at easing symptoms and averting potential complications. Notably, a novel medicine called Mavacamten has earned regulatory approval, including from the FDA, for patients grappling with significant pressure elevation within the left ventricular chamber due to HCM. This innovative drug has exhibited efficacy in alleviating symptoms and reducing pressures. For a deeper dive into this topic, we invite you to watch our informative YouTube video below.

- Implantable devices: A pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) may be recommended for people who have arrhythmias or are at higher risk, such as those with significantly greater left ventricular size/mass or demonstrate episodes of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT). For more information on VT, please check out our article here.

- Surgery: In severe cases, surgery may be needed to remove part of the thickened heart muscle obstructing blood flow. This procedure is known as surgical septal myectomy.

- Alcohol septal ablation: This may have a role for select patients, although is less frequently used first-line nowadays.

- Lifestyle changes: Avoiding strenuous physical activity and reducing stress can help prevent symptoms and complications. Avoiding dehydration can also assist.

Conclusion

In conclusion, HCM is a common genetic condition that affects the heart’s ability to pump blood effectively. While many people with HCM have no symptoms, it can lead to various complications, including arrhythmias, heart failure, and obstructive HCM. Treatment focuses on managing symptoms and preventing complications, including medications, implantable devices, surgery, and lifestyle changes. If you or someone you love has been diagnosed with HCM, it is important to work closely with a healthcare professional to develop a treatment plan tailored to your needs.