During my follow-up consultations with patients after their discharge from the hospital following treatment for a heart attack, a common theme emerges: many recount initially attributing their chest discomfort to heartburn or indigestion. Often, they confess to delaying seeking help after trying over-the-counter anti-reflux treatments or resorting to home remedies like drinking milk.

This anecdote underscores the critical need for clear understanding and prompt recognition of the differences between heartburn and angina, two conditions that can mimic each other but necessitate vastly different approaches to treatment and management.

This article will explore the complexities of heartburn and angina, examining their similarities and differences and the importance of timely medical intervention to ensure optimal outcomes for individuals experiencing chest discomfort.

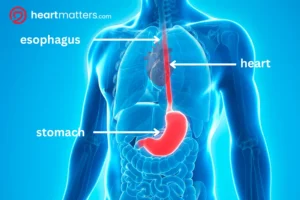

The Anatomy of the Esophagus

The esophagus, often called the food pipe, is a muscular tube extending from the throat to the stomach. Its primary function is transporting food and liquids from the mouth to the stomach through coordinated muscular contractions known as peristalsis. Located behind the trachea and in front of the spine, the esophagus traverses the chest and abdomen, passing through the diaphragm before connecting to the stomach.

Despite its seemingly simple structure, the esophagus facilitates digestion by ensuring food’s smooth passage to its destination.

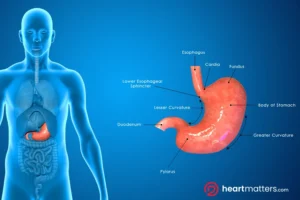

The Anatomy of the Stomach

Situated in the upper abdomen, nestled between the esophagus and the small intestine, lies the stomach—a pouch-like organ responsible for further breaking down food and mixing it with gastric juices and enzymes. Structurally, the stomach consists of four main regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus, each with distinct functions in the digestive process.

The cardia serves as the entry point from the esophagus, while the fundus acts as a reservoir for food storage. The body of the stomach is where most of the digestive activity occurs, as it secretes gastric acids and enzymes to break down food into a semi-liquid mixture called chyme. Finally, the pylorus regulates the release of chyme into the small intestine, where further digestion and nutrient absorption occur.

Together, these anatomical features enable the stomach to play a pivotal role in the digestion and absorption of nutrients essential for overall health and well-being.

What is Heartburn?

Heartburn, also known as acid indigestion or pyrosis, occurs when stomach acid refluxes into the esophagus, causing a burning sensation in the chest or upper abdomen (often called the epigastrium).

Key features of heartburn include:

Burning sensation: Patients often describe a burning discomfort in the chest or upper abdomen, which may worsen after meals or when lying down.

Acid brash: Some individuals may experience regurgitation of acidic or bitter-tasting fluid into the mouth.

Radiating pain: Heartburn can occasionally radiate to the back, mimicking symptoms of angina.

Associated factors: Factors such as a history of peptic ulcers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use, or consumption of trigger foods (e.g., spicy or fatty foods) can exacerbate heartburn symptoms.

Causes of Heartburn

Understanding the causes of heartburn is crucial for effective management and prevention. Here are some key factors that can trigger heartburn:

- Diet: Certain foods and beverages, such as spicy dishes, citrus fruits, tomatoes, chocolate, caffeine, and alcohol, can relax the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and increase stomach acid production, leading to acid reflux and heartburn.

- Lifestyle habits: Smoking, obesity, and eating large meals or lying down immediately after eating can exacerbate heartburn symptoms by putting pressure on the stomach and promoting acid reflux.

- Medical conditions: Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hiatal hernia, gastroparesis (where there is delayed emptying of the stomach contents into the small intestine), and peptic ulcers are among the medical conditions that can predispose individuals to heartburn.

- Medications: Certain medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, and bisphosphonates (used for the treatment of osteoporosis), can relax the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) or irritate the esophagus, contributing to heartburn symptoms.

Diagnosis of Heartburn

Diagnosing heartburn involves a comprehensive evaluation to pinpoint the underlying cause and assess the severity of acid reflux. The diagnostic process typically includes the following steps:

- Medical history review: Healthcare providers will inquire about the nature of symptoms, dietary habits, lifestyle factors, and any medications or medical conditions that may contribute to heartburn.

- Physical examination: A thorough physical examination may be conducted to assess for signs of underlying conditions and to evaluate overall health.

- Diagnostic tests: Depending on the severity and duration of symptoms, healthcare providers may recommend additional tests to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other conditions. These tests may include:

- Upper endoscopy: This procedure involves inserting a thin, flexible tube with a camera (endoscope) into the esophagus to visually inspect the lining of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum for signs of inflammation, ulcers, or other abnormalities.

- Esophageal pH monitoring: This test measures the acidity level in the esophagus over a period of time to evaluate the frequency and severity of acid reflux episodes.

- Imaging studies: X-rays, CT scans, or other imaging modalities may be used to assess the structure and function of the esophagus and stomach, helping identify any underlying conditions contributing to heartburn.

Differentiating Heartburn from Angina

While heartburn arises from gastric issues, angina is a symptom of underlying heart disease and requires immediate medical attention.

Distinguishing features of angina include:

Characteristic pain: Anginal pain is often described as pressure, squeezing, or tightness in the chest, which may radiate to the neck, jaw, shoulders, back, or arms.

Associated symptoms: Angina may be accompanied by additional symptoms such as shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, sweating, or palpitations.

Triggers: Angina episodes may be precipitated by physical exertion, emotional stress, or exposure to cold temperatures. Any abrupt-onset symptoms that make you feel unwell, sweaty, or uncomfortable in and around the chest, such as pain, tightness, discomfort, or shortness of breath, need to be assessed urgently.

Importance of Seeking Prompt Attention

While heartburn is often benign, treating any chest discomfort seriously is crucial, particularly when it resembles symptoms of angina. If you experience persistent or severe chest pain, accompanied by symptoms such as shortness of breath, sweating, or nausea, or if you have risk factors for heart disease, seeking prompt medical attention is imperative. When in doubt, it’s always best to get checked out by medical or health staff who can provide prompt attention and proper evaluation.

Any chest discomfort should be taken seriously, especially when it mimics symptoms of angina. It’s essential to seek prompt medical attention if you experience persistent or severe chest pain, associated symptoms such as shortness of breath or sweating, or have heart disease risk factors.

A thorough assessment is paramount when evaluating patients with symptoms suggestive of indigestion but also needing to rule out a cardiac cause. It begins with a quick yet comprehensive history-taking process, during which clinicians inquire about the nature and quality of the pain, its onset, duration, and exacerbating or alleviating factors.

Associated symptoms such as shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, and pain radiating to the arms, jaw, or back will receive specific attention. During the clinical examination, signs of heart failure, tachycardia, or arrhythmias will be carefully noted.

Preliminary Investigations

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) offers valuable insights into cardiac function and helps detect any abnormalities indicative of a potential acute heart attack (acute myocardial infarction). Emergency medical personnel or hospital staff will promptly administer this test to assess the urgency of your condition and triage your presentation accordingly.

Further diagnostic investigations may include measuring cardiac enzymes, such as troponin, echocardiography to assess cardiac structure and function, stress testing to evaluate cardiac performance under exertion, and imaging studies, such as CT angiography or invasive angiography if concerns about possible myocardial infarction persist. This comprehensive approach ensures that gastrointestinal and cardiac etiologies are thoroughly evaluated, guiding appropriate management and patient safety.

Treatment Strategies for Heartburn

Effective management of heartburn involves a multifaceted approach aimed at relieving symptoms, reducing acid reflux, and preventing complications. Here’s a detailed overview of treatment options:

Lifestyle Modifications:

-

- Dietary changes: Avoiding trigger foods such as spicy, acidic, or fatty dishes and carbonated beverages can help minimize acid reflux and alleviate heartburn symptoms.

- Eating habits: Eating smaller, more frequent meals and avoiding lying down immediately after eating can reduce pressure on the stomach and lower esophageal sphincter (LES), minimizing the risk of acid reflux.

- Weight management: Diet and exercise can help maintain a healthy weight, alleviate pressure on the abdomen, and decrease the frequency and severity of heartburn episodes.

- Elevating the head of the bed: Raising the head by 6 to 8 inches can help prevent acid reflux during sleep by keeping the stomach contents below the esophagus.

Over-the-Counter (OTC) Medications:

-

- Antacids: OTC antacids such as Quick-Eeze, Gaviscon, Mylanta, Tums, Rolaids, or Maalox can provide relief by neutralizing stomach acid and alleviating heartburn symptoms.

- H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs): Drugs like ranitidine (Zantac), famotidine (Pepcid), and cimetidine (Tagamet) reduce stomach acid production, providing longer-lasting relief from heartburn. Always check with your healthcare professional if these are suitable for your condition.

Prescription Medications:

-

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): Prescription-strength medications such as omeprazole (Prilosec), esomeprazole (Nexium), and lansoprazole (Prevacid) suppress gastric acid production, offering more effective and long-term relief from heartburn and acid reflux.

- Prokinetics: These medications, such as metoclopramide (Reglan), help improve esophageal motility and enhance gastric emptying, reducing the frequency of acid reflux episodes.

- Surgical Intervention:

- Fundoplication: In severe cases of GERD or when medications fail to provide relief, surgical procedures like fundoplication may be considered. During this procedure, the upper part of the stomach is wrapped around the LES to strengthen it and prevent acid reflux.

- LINX device: An alternative to traditional surgery, the LINX device is a small, flexible ring of magnetic beads placed around the LES to reinforce its function, prevent acid reflux, and allow food to pass through normally.

Consult with a healthcare professional to determine the most appropriate treatment approach based on the severity of symptoms, underlying medical conditions, and individual preferences. Regular follow-up appointments may also be necessary to monitor treatment effectiveness and adjust the management plan. By implementing a tailored treatment regimen, individuals can effectively manage heartburn, improve their quality of life, and reduce the risk of complications associated with acid reflux.

Management of heart attack (acute myocardial infarction)

Management of cardiac chest pain causing an acute myocardial infarction (MI) requires prompt and comprehensive intervention to minimize myocardial damage and improve outcomes. Upon suspicion of an acute MI, immediate administration of sublingual nitrates can help relieve chest pain by dilating coronary arteries and improving blood flow to the heart muscle. Opioids such as morphine may also be administered for pain relief. Anti-emetics may also be given to alleviate nausea or vomiting associated with the pain.

In addition to pain management, supplemental oxygen may be provided. Aspirin is a cornerstone of acute MI treatment for all suspected cases of MI to inhibit platelet aggregation and reduce the risk of further clot (thrombus) formation. Urgent transfer to the hospital is imperative for definitive management, where a range of medications may be administered, including antiplatelet agents (e.g., clopidogrel, ticagrelor) and heparin to prevent further clot formation.

Depending on the hospital’s resources and the patient’s clinical status, activation of the cardiac catheterization lab for immediate coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) may be warranted. PCI involves inserting a catheter with a balloon at its tip into the blocked coronary artery to restore blood flow, often accompanied by stent placement to maintain vessel patency. In cases where access to a cath lab is unavailable or delayed, thrombolytic therapy may be considered an alternative to dissolve the clot and restore blood flow. This involves an intravenous injection of a potent clot-busting drug. However, thrombolysis carries a risk of bleeding complications and is generally reserved for situations where PCI cannot be performed expeditiously. Overall, the management of acute MI necessitates a coordinated and timely approach to minimize morbidity and mortality associated with this life-threatening condition.

Conclusion

Understanding the differences between heartburn and angina is crucial for timely intervention and appropriate management. While heartburn can often be managed with lifestyle changes and medications, angina requires urgent medical attention to rule out serious cardiac issues. If you experience any chest discomfort or associated symptoms, don’t hesitate to seek prompt medical evaluation to ensure your health and well-being. Remember, it’s always better to err on the side of caution when it comes to matters of the heart.